Aisle 20, AR-15s, ammo; Aisle 21, Cheetos, Slim Jims; Aisle 22. Primary Care…

Walmart announced Friday that it plans to provide “full primary care services” to consumers nationwide within five to seven years.

The retail giant made headlines in 2011 when it sent 14-page letters to health providers and companies requesting information to help it establish “the largest provider of primary health care services in the nation.” However, the company quickly clarified that it was “not building a national, integrated, low-cost primary health care platform.”

Speaking at the Foundation of Associated Industries of Florida’s 2013 Health Care Affordability Summit, Marcus Osborne—Walmart’s vice president of health and wellness payer relations—was asked whether the retailer plans to pursue retail clinics in rural areas.

He said, “That’s where we’re going now: full primary care services in five to seven years.”

Osborne added that Walmart’s clinics will be in underserved, urban areas because the chain has many stores in those areas. “One of the areas we’re highlighting is where there isn’t access to care,” he said. (So, if we were to get a Walmart in the old Grand Union space? Hmmm.)

Can Walmart provide us with primary care as efficiently as it provides us with unnecessary plastic objects and junk food? I think the answer is probably yes. It might not be the same kind of one-on-one doctor-patient relationship we long for, and it might involve more urgent care from midlevel providers and less preventive care or chronic disease management from physicians, but I think that a business like Walmart, that runs an efficient, national corporation, could find a way to disrupt things and deliver some level of care in a more efficient manner. For that matter, I bet the Cheesecake Factory could as well.

But here’s the catch. It can do so only if it does what other retail medical outlets are already doing: ignore the third-party payers. Almost everything that’s wrong with our health care system is the direct result of third-party payment. In response, there are a lot of people reinventing healthcare, in small corners around the country, and showing great improvements in efficiency, quality and patient satisfaction, by opting out of the third-party payer status quo. If Walmart were to negotiate directly with businesses and customers to provide care on its own terms, and not have to bow to health insurance companies like the rest of us do, I think they could indeed make a big impact. I just hope they do not skimp on quality. I don’t mind buying a plastic onion chopper that is going to break in 9 months, when I know I am getting it for ¢50, but I do not want discounted services when my child is sick and seeing their doctor.

I am not saying that our problems are being created by health insurance. There is nothing in principle wrong with insurance. The source of our problems is using insurance companies to pay medical bills. It’s insurance companies acting pro emptore — in place of the buyer. When this happens, a number of things begin to change, all of them bad:

- The provider becomes the agent of the insurance companies, rather than of the patient — and this changes the practice of medicine to the third-party’s view of how it should be practiced.

- The provider no longer has to compete for patients based on price.

- Absent price competition, the provider no longer competes for patients based on quality.

- Overall, the provider’s incentive is to maximize against reimbursement formulas rather than provide low-cost, high-quality care.

- The third-party payer further maximizes profits by adding levels of regulatory smokescreen, making it harder for providers to be reimbursed for what they’re owed in the first place.

- Causing the providers to work harder, see more, and further sacrifice quality.

Walmart has clearly been testing the waters for a couple of years, even prior to their bombshell announcement in November, 2011. A National Center for Policy Analysis Health Policy blog summed up their efforts almost two years ago:

This past weekend, Wal-Mart was offering health care screenings to male customers at no charge. Sam’s Clubs across the country gave any customer willing to take the time:

BMI Index measurements, Blood pressure tests, Cholesterol readings, PSA (prostate cancer) tests, and TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) tests. And that’s not all. Sam’s Clubs have more free screenings planned for the future. Here’s the schedule:

July: Kids Health Screenings August: Vision Health Screenings September: Diabetes Screenings October: Women’s Health Screenings November: Digestive Health Screenings Further, at the store I visited there was no waiting. And if there happened to be a wait, I suspect it would be handled the way Wal-Mart handles prescription drugs. In order to reduce both the time cost and the money cost of care, Sam’s Club Pharmacy promises:

Hundreds of generic prescriptions for just $4, Prescriptions filled in just 20 minutes, and Text alerts to tell you when your prescription is ready, so you can shop while you wait.

So, is this a good thing or a bad thing? I don’t know. Instinct says that replacing a traditional doctor with a Walmart branded one is a bad thing. But on the other hand, the system is so broken that before long, the traditional doctors will be offering laser hair removal, weight loss clinics, Botox injections and Lasik eye surgery instead. We might need the Waltons to come along and bust things up a bit.

A 21 State Salute

Today’s Globe has a front-page above-the-fold article about Nantucket Cottage Hospital: “21 States Take Aim at Mass. Hospital’s Medicare Windfall-Nantucket’s Tiny Hospital that funnels hundreds of millions to other institutions.”

The article makes it sound like we’re a money laundering operation cleaning up dirty wads of cash as they come in to the state from Medicare.

“…the 19-bed hospital on the tony island…has become a national symbol of inequity and political machinations in the way the federal government reimburses hospitals for treating Medicare patients.”

The reporter tells the story as if Massachusetts hospitals teamed up with Senator Kerry in 2011 and found a way to game the complicated Medicare reimbursement system. And now, after an Institute of Medicine report from last summer, which named the shift in reimbursement (from other states to Massachusetts) the “Nantucket Effect,” 21 other state’s hospital associations finally figured out the game, and the game is up.

“…a coalition of 21 states is seeking to reverse the windfall, calling it the “Bay State boondoggle,” the product of “Yankee ingenuity” — the artful manipulation of obscure payment formulas.”

I cannot remember exactly when, but before our affiliation with Partners Healthcare in 2008, NCH had already declared as a Critical Access Hospital. This reform was put in to place to help save rural hospitals that are suffering across the country. If you met the criteria (which centered around hospital size and proximity to other hospitals), Medicare agreed to reimburse you based on your costs alone, rather than on the complex formulas this article discusses. For NCH, this was a big benefit, given our high costs of doing business.

But even back then, there was a formula that determined the reimbursement rates for a state’s hospitals, and it included the “Rural Wage Index,” a calculation of how expensive it is to do business at the most rural hospitals in the state. When a hospital opts for Critical Access designation, it is no longer used in the calculations of the Rural Wage Index.

Partners did not come to Nantucket Cottage Hospital in 2008 wanting to acquire the hospital simply because they needed a small hospital on a tony island to fill out their portfolio. They didn’t ask NCH to give up their Critical Access designation, with the promise to make whole any losses they might incur as a result, just to be nice. This was their promise even back then, recapturing the hundreds of millions of dollars that had been diverted from state hospitals when that designation kicked in.

There was no attempt to game the system. Massachusetts Hospitals Association, along with the big hospital systems in the state, all noticed the checks from the government were getting smaller, researched it and realized why (our change to Critical Access designation) and found a quick and easy fix. Acquire NCH and drop the designation. Nothing wrong there.

To the 21 states crying foul now, I say, what took you so long? Don’t blame Massachusetts or Nantucket Cottage Hospital. Blame the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services that would even start with such an archaic formula to determine how much they should pay a hospital for taking care of sick, elderly people.

Anyone unfamiliar with it will not believe the rules involved with Medicare reimbursement to hospitals. To summarize, a hospital is not paid according to the services a Medicare beneficiary needs. They are paid according to the diagnosis. If you have Medicare, and are admitted with pneumonia, Medicare has already determined that a pneumonia ought to be good for 1.8 days of hospital stay (as long as you also have an IV in place and are receiving IV antibiotics). If your pneumonia is complicated, and you end up needing to stay an extra few days, there is no change in how much they pay. If you are 78 and otherwise healthy and independent, but too weak from the pneumonia to go home just yet, that is tough. Medicare will not pay more than the amount needed to cover the 1.8 days. The hospital has to decide whether to eat the added costs of your stay, or push you off to a nursing home.

Hospitals have to know that they’re going to get paid the 1.8 days, and have to bill Medicare accordingly. Some hospitals have as many Utilization Managers as they have nurses, in order to do this right. Reason is, if a hospital does it wrong, if they assume that since a patient has a comorbid diagnosis like a urinary tract infection means that they get 2.4 days of stay, instead of 1.8, and they’re in a gray area of the rules, then a private auditor, a Medicare-endorsed bounty hunter, can come to a hospital 3 or 4 years later, audit the books, interpret the rule in a way that best benefits it (while working on a commission), declare fraud, and insist on a refund with penalties! Seriously. The mafia is jealous of this arrangement!

And, finally, to make matters worse, the amount that Medicare will pay for the 1.8 days varies by locale, according to formulas like the one discussed in this article. A formula so complex that it took these 21 states 4 years to realize why they were losing money!

So, don’t come pointing fingers at Nantucket! These days you hear a lot about “entitlement reform” and reporters and pundits are usually talking about how the Republicans want the Democrats to agree to spend less on healthcare for the elderly. To cut spending. But this article shows that we truly do need to reform this entitlement. Not at the expense of the beneficiaries. But to the advantage of hospitals across the country trying to survive on Medicare payments. If the rules could be reformed, made simpler, hospitals could cut costs dramatically and do better, even, with lower reimbursements (by replacing administrators with lower-cost healthcare providers), and we could use the money saved to pay down the debt, to mint $1 Trillion coins, to improve access to mental health and preventive services, or even to cover the pending costs of Alex Jones’ therapy!

(photo from Flickr user Images_of_Money)

UPDATE: The states have delivered a letter to President Obama asking that Nantucket Cottage Hospital be placed on a floating barge, so as to not be considered a Massachusetts hospital. Read about it here.

An Rx for IT

Many of you know that, since this past summer, I have been working in a consulting role with a medical software company in Westborough, MA called eClinicalworks. I have learned a great deal about the role of technology in the delivery of healthcare.

Having 5 months of experience in the industry now certainly qualifies me to tell you exactly what is wrong with it and where the industry needs to go from here. Right?

Logic has always dictated that the most important reason to use computers is to lower costs and increase efficiency. A new study by the RAND Corporation shows this is simply not true. From the NYTimes yesterday:

“The conversion to electronic health records has failed so far to produce the hoped-for savings in health care costs and has had mixed results, at best, in improving efficiency and patient care, according to a new analysis by the influential RAND Corporation.”

Actually, the most important reason to use electronic medical records is to improve the health of our patients, to guard against errors, and to improve the overall experience for patients. Like Facebook, technologies can (in an ideal world) help us, as doctors, better communicate with our patients and to access their medical history (their “Timeline” as it were), and make the experience better and more streamlined for doctors and patients alike.

But, up to now, medical software hasn’t been designed to engage patients, it has been designed to improve physician billing. More attention has been paid to maximizing communication with payers and to making it easier to document an encounter to support the complexity needed for higher billing codes. Most EMRs will flawlessly communicate a charge electronically to any one of hundreds of health insurance companies, but still are unable to import your medical history and put the data in the right place in your chart!

People typically spend less than one hour a year with their doctors (and 8,759 hours per year checking their Facebook newsfeed and looking for cute pics of kittens on the Internet). Some people even skip that one-hour of visits all together. Combine this with studies that have shown that patients forget around 85% of what a doctor says during visits, ant that means, at best, my patients remember about nine minutes of everything I say per year.

What if that information had a chance to sink in? What would that do for our country’s health? What if instructions and education made it past the checkout window? What if we could remind our patients to take their pills or exercise? Send contextual health information in between visits? Prompt for important preventive procedures and tests? Of course, there’s all kinds of technology that exists to help us communicate with one another, e.g., Facebook, Skype, or text messaging. But you see very little of that designed to safely and securely facilitate communication between doctors and patients. That’s what our industry needs to be working on, tools to safely and securely mimic these types of technologies to improve the communication. (Part of the problem is, of course, health insurance doesn’t reimburse for such disruptive technologies and there is, therefore, less incentive for doctors to try, and little incentive for IT companies to work on this.)

Yet, this is what I am working on with eClinicalworks, new software to try and maximize the experience, and to make such communication easy and efficient for the doctors, and more accessible for the patients. I find it to be very rewarding work and I cannot wait to start using the fruits of our labor!

What about Nantucket? Could technology help to improve the healthcare delivery on Nantucket?

I think the answer is Yes and No or, better yet, “ought to” and “it ain’t going to happen!”

Right now, Nantucket is just another good example of the disease that is affecting Health IT nationally, the inability to exchange data between different systems. It is such a shame that this industry is so far behind other industries, such as the financial or shipping sectors. When I use my Stop & Shop card to purchase a box of Kraft Mac & Cheese, Kraft knows this, somehow, and automatically sends $0.03 as a refund to an organization called UPromise, which then deposits it into a 529 College Savings Fund I have with Fidelity (because I registered my S&S card with UPromise) and it shows up in my monthly emailed statement. And yet, if Dr. Lepore is out of town one day, and Dr. Butterworth sees one of his patients for an emergency, he is unable to see the record of that patient’s medicine allergies. This is unforgiveable (of our industry).

Nantucket’s health technology woes, like the nation’s as a whole, and are due to having multiple systems in place that do not talk to each other, causing a continued reliance on paper, making errors and oversights more likely to happen, and leading to inefficiencies in workflow.

The MGPO practices currently uses a record system called the LMR, which was written years ago for the physician practices at Mass General. Recognizing it’s difficulties in scaling to cover MGH’s expansion into new areas and hospital systems, as well as the trouble it has in integrating with other systems in place in their system as a whole, such as, the different systems for billing, and scheduling, and lab information, Mass General has recently signed a contract with Epic Systems to replace it with their software, and will spend over $600 million and 10 years to implement it! (And you wonder why your knee MRI is $3,000.)

My first concern about this is that if it is going to take 10 years to implement this, it’s hard for me to imagine the remote practices and smaller hospitals in the Partner’s system will be high on the list of priorities for installation. This will take a while.

My second concern is that Epic is a closed, legacy system. Using it, data communication (i.e., patient information) within Partner’s institutions should be improved. One database. One record. But Epic, as a closed system, is a shut door for this same data when it comes to communicating with other systems, e.g., smaller hospital systems, other ambulatory practices, radiology and lab centers, and even other systems using Epic.

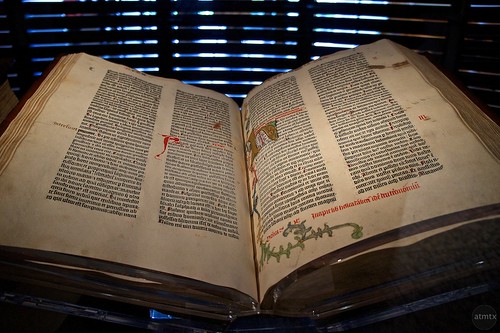

Finally, if it takes 10 years for them to implement it, I question whether or not this system will still be relevant. Ironically, even though it is a private company worth billions, Epic’s software is based on a computer language called MUMPS, the Massachusetts General Hospital Utility Multi-programming System, which was written 44 years ago, by scientists in an animal lab at Mass General! Forty-four years in computer programming years is akin to this haven been written as an addendum to the Gutenberg Bible! Since it is extremely challenging and costly for any organization that is not using it to interface with it, and since one of the biggest pushes in federal health regulation is towards the interchange of data, I question how relevant this software will be in 10 years. Certainly, if your goal was speed and efficiency, free and easy interchange of information, there are more modern “Cloud” technologies out there to be taken advantage of. But the problem is scaling these newer technologies to work in large hospital systems like Partners, and Johns Hopkins, and the Cleveland Clinic. And this is the niche Epic has created for themselves. This tried and true, if outdated, software makes it easier to customize large installations.

There was an interesting article in Forbes this past summer that discussed whether or not the hold Epic is developing on some of our larger hospital systems is a good thing or a bad thing for healthcare in general. My opinion is that closed systems are bad for healthcare as a whole.

In an ideal world, Nantucket’s hospital and handful of physician practices would have a unified software system in place that would allow for ease of use at the point of care, for patient online access to their records, secure messaging and improved communication with providers in between visits, and a safe but reliable and electronic exchange of information from the ER to the hospital to the lab to the doctor’s offices and to the patient. This system would also need to be open to communication from America, as it were, sending and receiving data from non-Partner’s and Partners hospitals (e.g., South Shore, Cape Cod, BIDMC, Dana Farber, Quest Labs, as well as MGH) and physicians.

Unfortunately, when it comes to Health Information Technology, there is no “ideal” world! Such a system does not exist. But as a small, contained health system, it would seem to me that if it were to be possible anywhere, it should be possible here! In the meantime, no good answers except to wait and see how long Epic takes to wash ashore.

Google + CDC

I love how Google technologies and traditional CDC surveillance can be used to quantify the severity of an outbreak like this year’s fle epidemic. Slate has an article, with frightening graphics, summarizing this.

PS. It’s not too late to get the vaccine!

An ER Physician’s take on guns

ER Physician and Army vet Dr. David Newman discusses gun violence in this NY Time op-ed:

I have sworn an oath to heal and to protect humans. Guns, invented to maim and destroy, are my natural enemy.

A Trilllllllllllllion Dollars

According to Matt Yglesias at Slate, one possible way to avert the upcoming financial Armageddon of the debt ceiling crisis would be to mint in platinum $1,000,000,000,000 dollar coins, and use them to finance the government:

“…a ludicrous but perfectly legal solution is also available to him. Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner can order the United States Mint to create large-denomination platinum coins—a $1 trillion coin, say, or a bunch of $10 billion coins—and use them to finance the government.

Really.

It all goes back to sub-section (k) of 31 USC § 5112 ‘Denominations, Specification, and Design of Coins.’ The opening subsections consists of boring specifications about the coins the United States issues. Subsection (k) says ‘The Secretary may mint and issue platinum bullion coins and proof platinum coins in accordance with such specifications, designs, varieties, quantities, denominations, and inscriptions as the Secretary, in the Secretary’s discretion, may prescribe from time to time.’

So there it is in black and white. Geithner can have the Mint create a $1 trillion coin. Then he can walk it over to the Federal Reserve and deposit it in the Treasury’s account. Then the government can keep sending out the checks—to soldiers and military contractors, to Social Security recipients and doctors who treat Medicare patients, to poor families getting SNAP and to FBI agents—it’s required by law to send—and the checks will clear. It’s a simple, elegant solution.”

Primary Care, Nantucket, Part 3…

After two somewhat damning posts on the state of Primary Care on Nantucket, I think it is only right for me to post on what is right.

We are lucky to have a staff of physicians and healthcare providers that are invested in the island, and good at what they do. In Drs. Butterworth, Koehm, Lepore, and Pearl, we have a group of physicians who have years of experience in medicine and, more importantly, small-isolated-island medicine. (I only left Dr. Steinmuller off of this list because I have yet to have the opportunity to talk with her or get to know her.) These doctors know what they know (and know well what is best addressed elsewhere, regardless of the inconvenience of getting there), and have adapted to the environment of managing the health of their patients within the constraints of the time available and the difficulties of small-town life.

Further, the hospital is staffed, for the most part, with a core group of islanders who are practiced in island medicine, good at what they do, and motivated to care for their neighbors, specifically, the nurses and the talented PAs that staff the ER.

I feel like these folks are all in the trenches, battling not only the wide array of illness and injuries that walk in the door, but the legion of changes in the delivery of healthcare that really makes it almost impossible for a place like Nantucket Cottage Hospital to keep their doors open. Look around New England; you will not find another hospital (or community health system) like Nantucket. By all accounts, we should have an ER and a helipad and nothing more. And yet, we all know, that would not do.

So, in spite of the financial and regulatory pressures of healthcare delivery, we are making it because of our smarts, adaptability, and personnel. And, for that, we are lucky. That has to be the hardest piece of the puzzle to put in place.

These are all the reasons why a recent Patient Satisfaction survey listed NCH as #10 (out of 176 in New England) in satisfaction. You can see the results here (scroll through to #10). Specifically, the survey said that NCH posted “…the highest communication scores in the Top 20, 93% of Nantucket Cottage’s patients said that their doctor always communicated well with them. Also, 88% of patients said they always received help with then asked–also the highest rating in the Top 20.” I’m proud to be a part of that.

Primary Care, Nantucket, Part 2…

“We’re short today. I need you two to answer the phones, see what the patients need, do your best to take care of them over the phone, and keep them out of the office, and out of the ER. If you have to call in something for them and tell them to call back in a couple of days, just do it.”

I overheard this speech (paraphrased above) one morning last winter from our temporary office manager, placed in the office by our Boston supervisors, to our practice’s two Registered Nurses, just as the clock flipped to 8:00 am and the phone lines began to light up. At first glance, this was no ordinary day. It was in the middle of the flu season, one of our provider’s was out of town, and another local doctor was out of the office with an unexpected illness. And the day was starting with all available appointment slots full. But in actuality, this was the dead of winter, nowhere near the peak season when our average daily population increases 5-fold, and not too atypical after all.

The desperate (or at least out-of-luck) patients were calling in at precisely 8 am because they had been instructed to do so the day before, the last time they called for an appointment and were told that same day slots are held until mornings and that the next scheduled appointments were at least 3 weeks away.

Two valuable clinical resources, experienced RN’s who are very good at their job, were going to spend the better part of the day apologizing and trying to keep patients from coming in to be seen in person which, under the guidelines of health insurance contracts, is the only way the practice could recoup the costs of having two RNs sitting at their desks answering phones. From a business point of view, it doesn’t take a Harvard MBA to understand that this is not sustainable, especially when the practice was already paying a significant share of net revenue for the management that had no option but to suggest this workaround.

From a medicine point of view, trying to manage urgent health issues over the phone with nurses, is sub-optimal healthcare. And, if there are no appointments available for urgent issues, there certainly are no appointments available for preventive medicine visits. No time to call patients and go over lab results from the previous week. No time to look for patients with chronic disease conditions that are not following through with their care plan. No time to tack on a little education and guidance to the end of each visit.

Join me on the hamster wheel, we’re just getting started:

…and no time to use an inefficient electronic medical record to document each of these visits in a way that maximizes reimbursement from the same health insurance companies (and government payers) that burden us with this system in the first place, which means…

…less money to provide for that manager’s and those RN’s salaries, which means…

…more pressure from supervisors, to see MORE patients during the day, to open up more appointment slots, which means…

…less time with each individual patient, which means…

…less focus on chronic medical issues, and more focus on the problem at hand (“treat and street”), which means…

…poor management of chronic medical conditions, which means…

…increased need for urgent care services, which means…

…increased demand for appointment slots, which means….

Trust me, like a hamster wheel, I can keep this going until I fall over in exhaustion.

And that is what happened to me last Spring.

Primary Care, Nantucket, Part 1…

I have a new friend on the island. He’s a healthy middle-aged guy who moved here in the past year. His only health issue is hypertension, and he has been on a blood pressure medicine for 5-6 years; he tells me his blood pressure has been well-controlled since being diagnosed, starting the medicine, and making some lifestyle changes. Saw his former doctor last year before his move, but had not needed to see a doctor on island until recently. He works with his hands and works hard, has a family, and had been too busy to think about it.

Two to three months ago, however, he injured his back at work. Only serious enough to keep him out of work for a week or so, but enough to make him think about going to see a doctor. He called 3 local doctor offices was either told that the doctor isn’t taking new patients, that there isn’t an appointment available, or that the office doesn’t handle Workman’s Comp cases. He went to the ER for treatment, and learned that his new health insurance has a $250 copay for ER visits.

While in the ER, he was told that his blood pressure was high, and that he should “consider” increasing the dose of the blood pressure medicine. He doesn’t get a new prescription for this, however.

His back slowly improves, he returns to work. He began taking two of his blood pressure pills every morning, instead of one, but soon afterwards, he felt noticeably more fatigued throughout the day. It was harder to get through a day’s work. He is smart enough to realize that this could’ve been due to the changed dose of his medication. So, he went back to taking one pill a day. Now, however, only had 2 weeks of medicine left on his current prescription. No more refills.

He called the local doctors once again. Out of the five local primary care doctors, he found only one willing to take him as a new patient, but the first appointment available was not for 4 weeks. Not wanting to spend another $250 in the ER, he began to cut his blood pressure pills in half, in hopes of stretching them out and making them last until the appointment.

When the day came, he took an hour off work for his late morning appointment. After checking in at the front desk, he waited 45 minutes before being taken back to the exam room. As the time passed, he became more and more anxious about work responsibilities and the day’s tasks. When he was first seen by the nurse, she mentioned his blood pressure was high, and left him to think about this for another 10 minutes before the doctor came in. He was now anxious enough to get back to work that, after his 10 minutes of face time with his new doctor (including, he says, about a 10-second listen to his heart with a stethoscope, but no other examination), and it was suggested that he increase the dose of his medicine, from 1 pill a day to 2, he decided not to go in to details about how he felt on the higher dose of the medicine and that he had only been taking a half-dose in the 4 weeks leading up to the appointment. He needed to leave.

I was talking with him last week, about a month after that appointment. He decided on his own to pick up the new prescription he received, now for twice as many pills per month as he had been taking, and take them one a day as he had been doing, and enjoy that the prescription would last twice as long and he would not need to return to see the doctor for a while.

I loaned him a blood pressure cuff and suggested he monitor his blood pressure for a week or so and get back to me.

That week, without the pain he had had in his back when he went to the emergency room, and while taking the medication as it had been originally prescribed, and without the anxiety that comes with sitting in a doctor’s office for an hour to spend 10 minutes with a doctor just to get a refill, his blood pressure readings were all normal. He was fine.

And this is Primary Care on Nantucket. This is why I was all too happy to leave the practice I had had here for 12 years, and to take a break from medicine all together.

As for blame? It doesn’t belong to the physician, or to the Emergency Room. You can only do so much with the time that you have, and under the regulatory constraints placed by health insurance and governmental payers.

Nantucket is drastically underserved by Primary Care Providers. Nationally, we have 100 primary care providers (PCPs) per 100,000 people. Massachusetts has 129 PCPs per 100,000 (and yet, with our precursor to Obamacare already in place, about half of the PCPs in the state are no longer taking new patients). The Cape has 99/100,000. The Vineyard has 113/100,000.

If you count Drs. Butterworth, Koehm, Lepore, Pearl, and Steinmuller, and you assume a year-round population of 10,000 (discounting, even, the population swell in the summer), then Nantucket is covered at a rate of 50 PCPs/100,000 people.

THAT is the problem. The delivery of primary care on the island is the single most important health concern for the island. It is not the age or appearance of the hospital. It is not the availability of specialists like cardiologists or endocrinologists. It is the simple fact of not being able to see a doctor (that knows you) when you need to see a doctor.